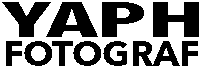

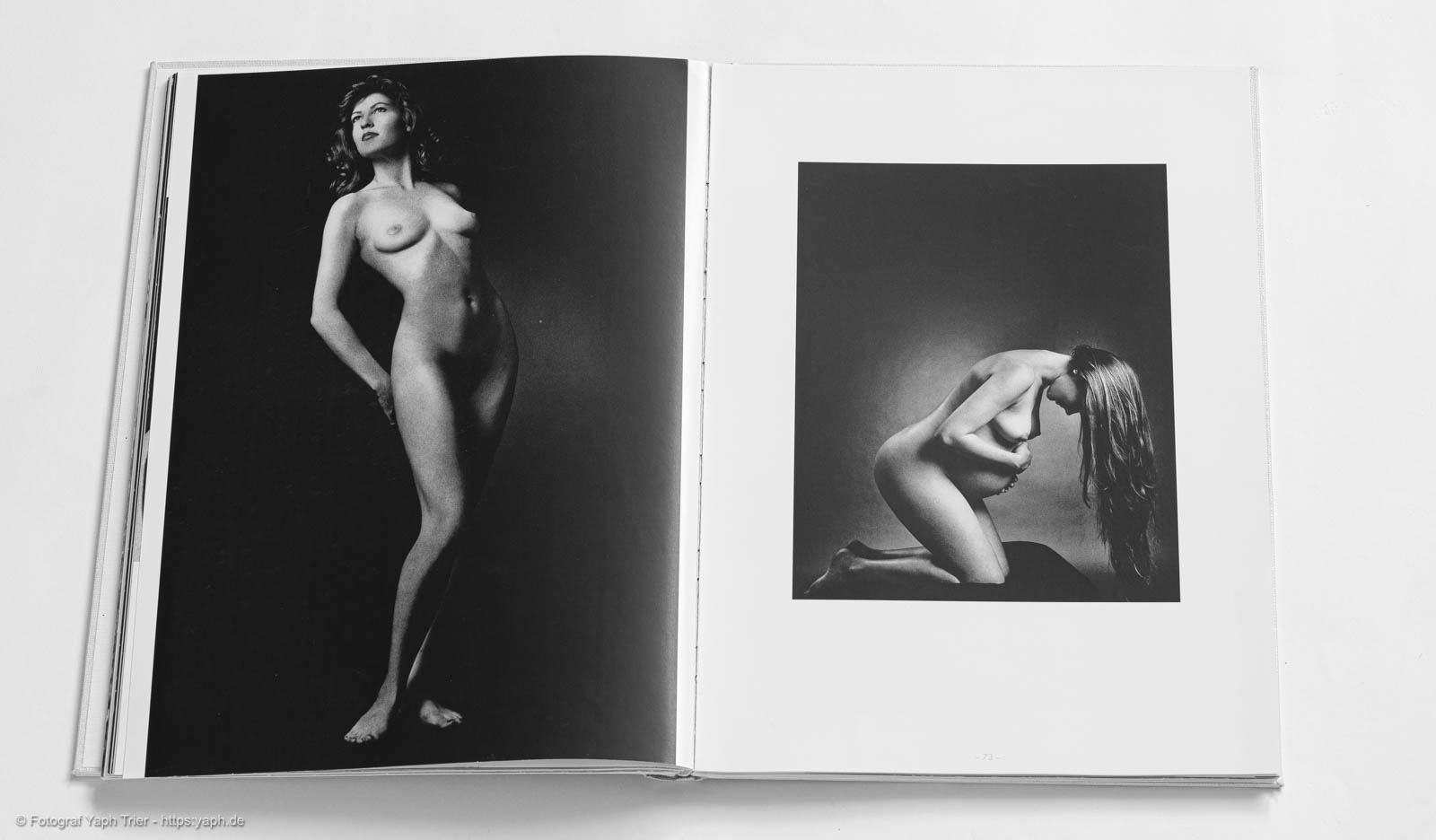

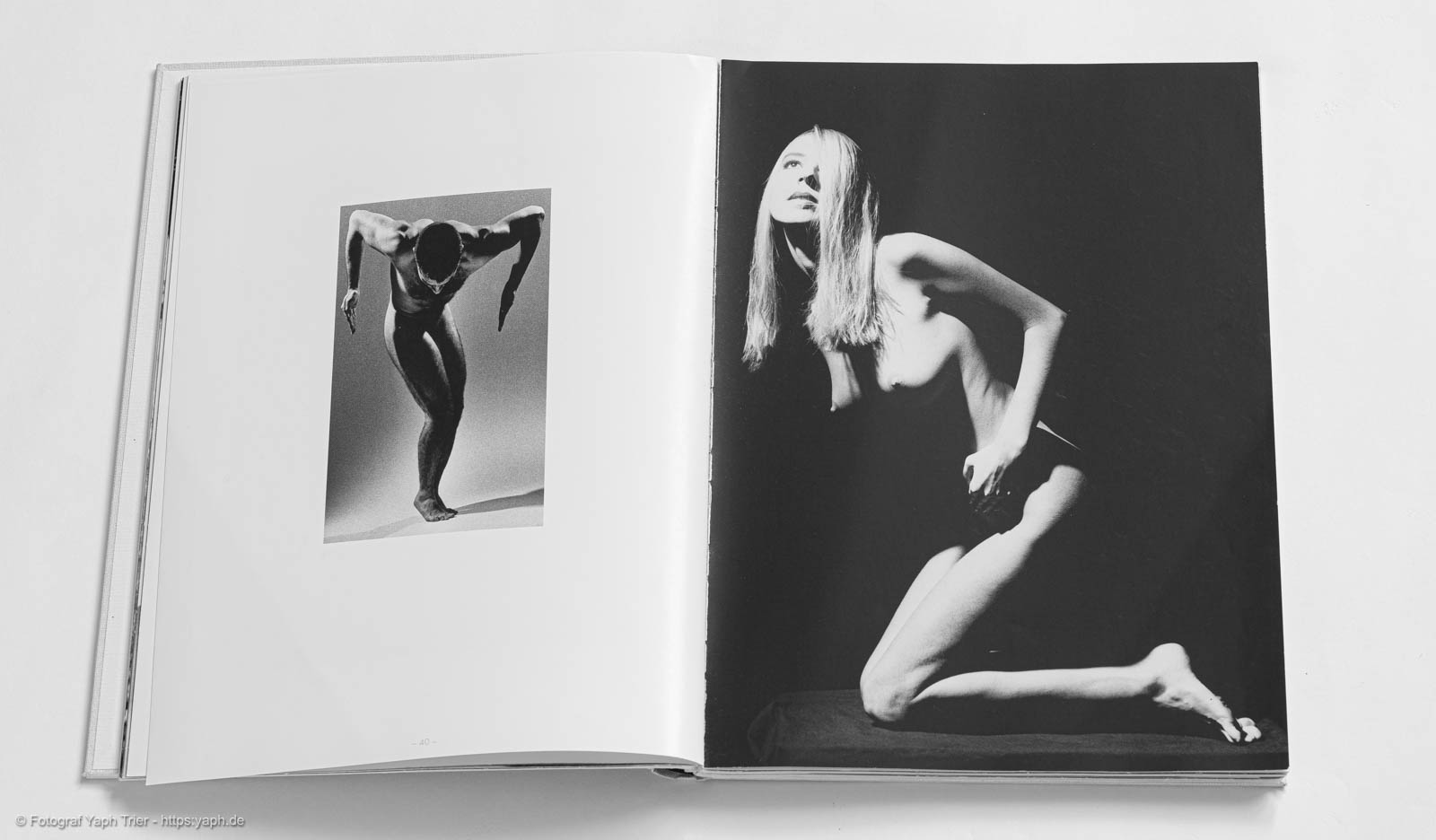

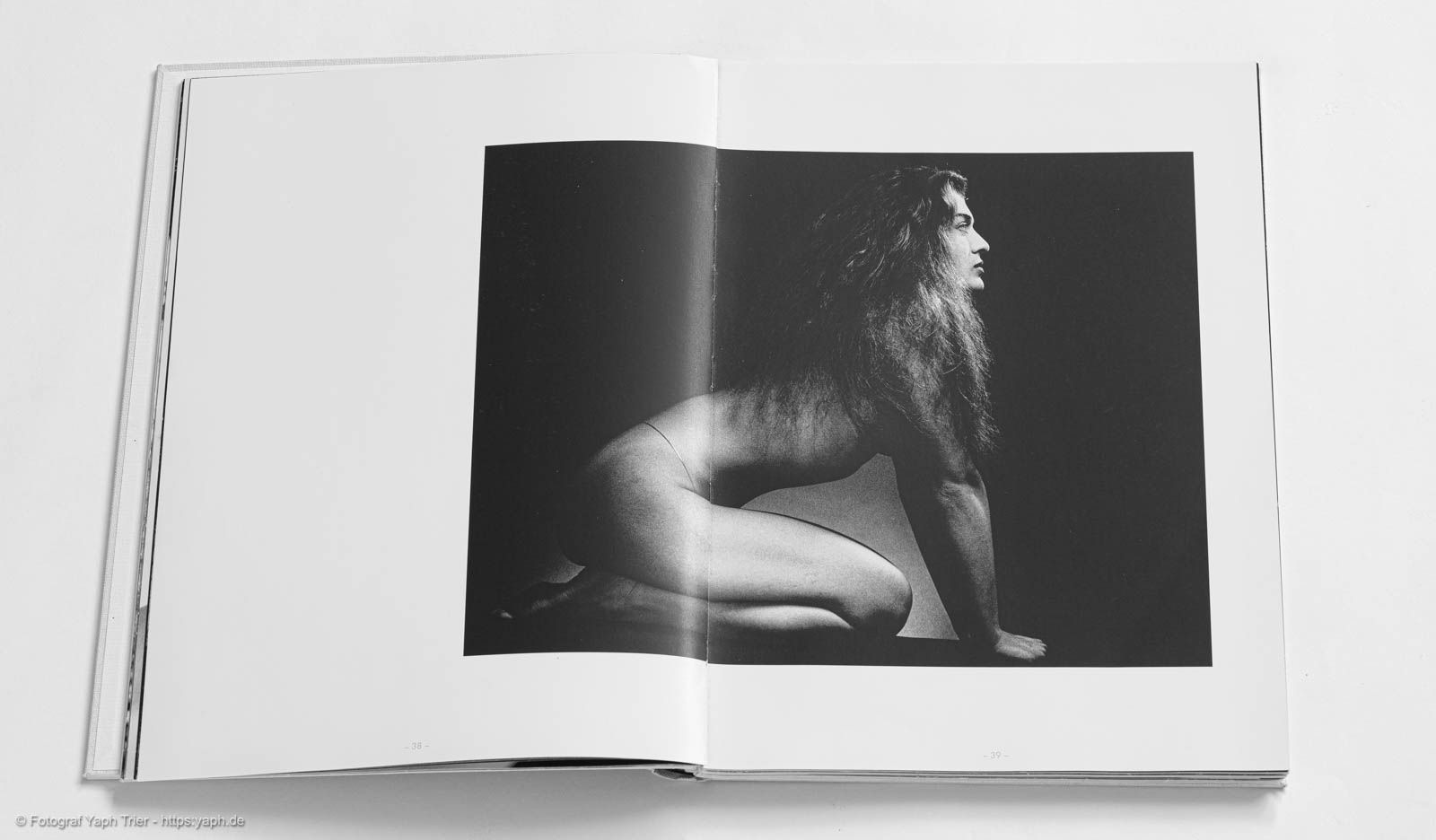

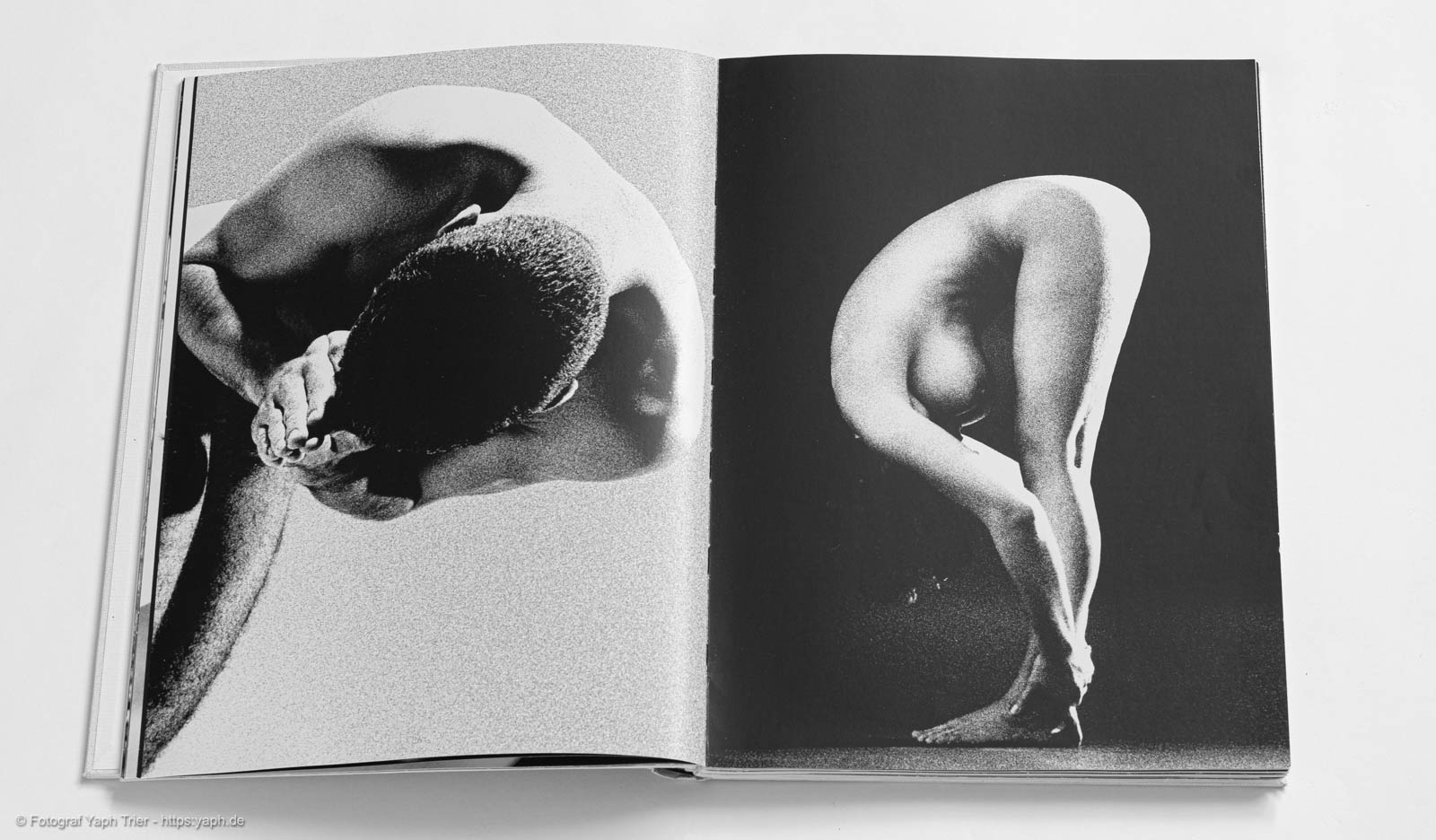

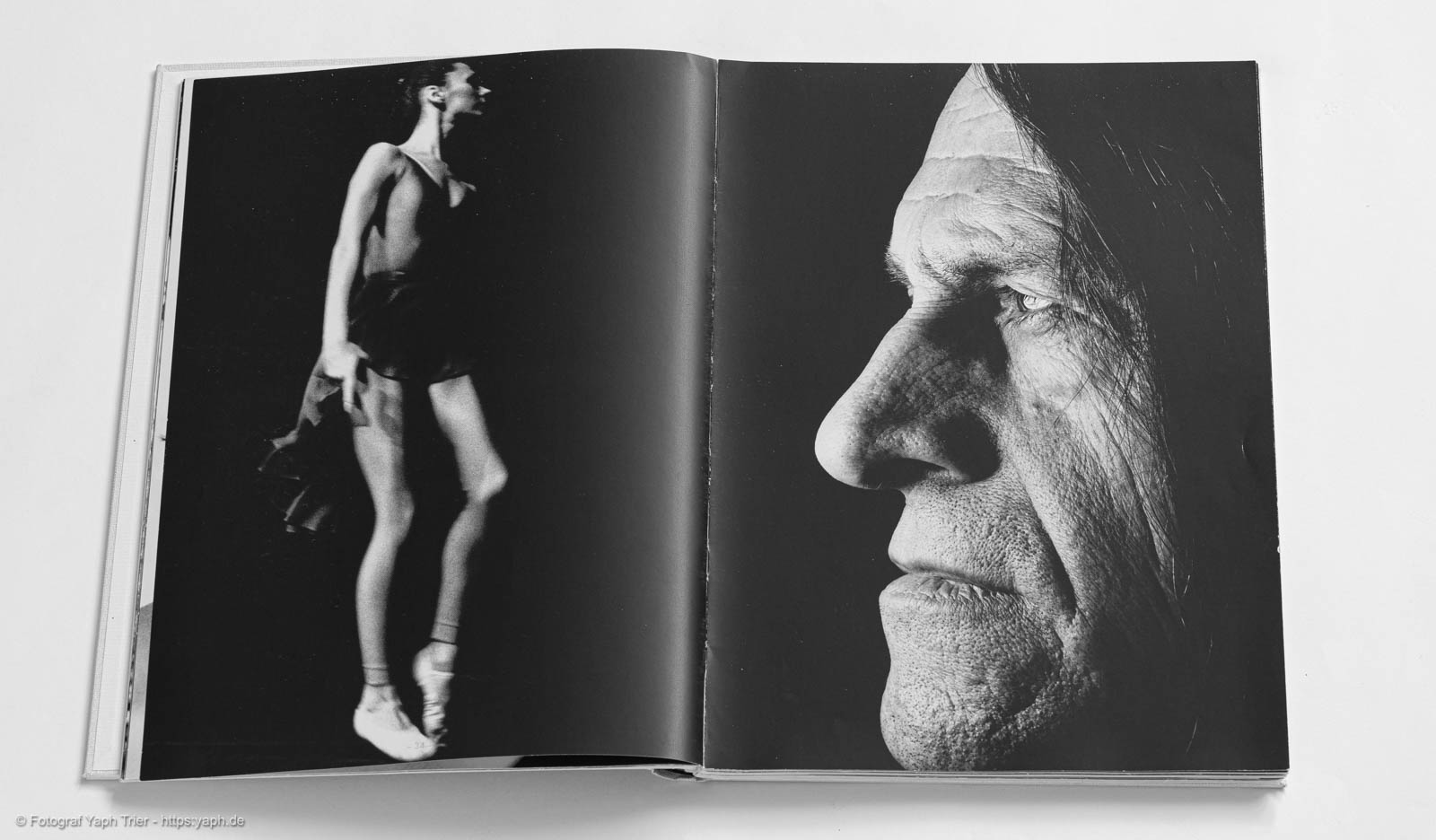

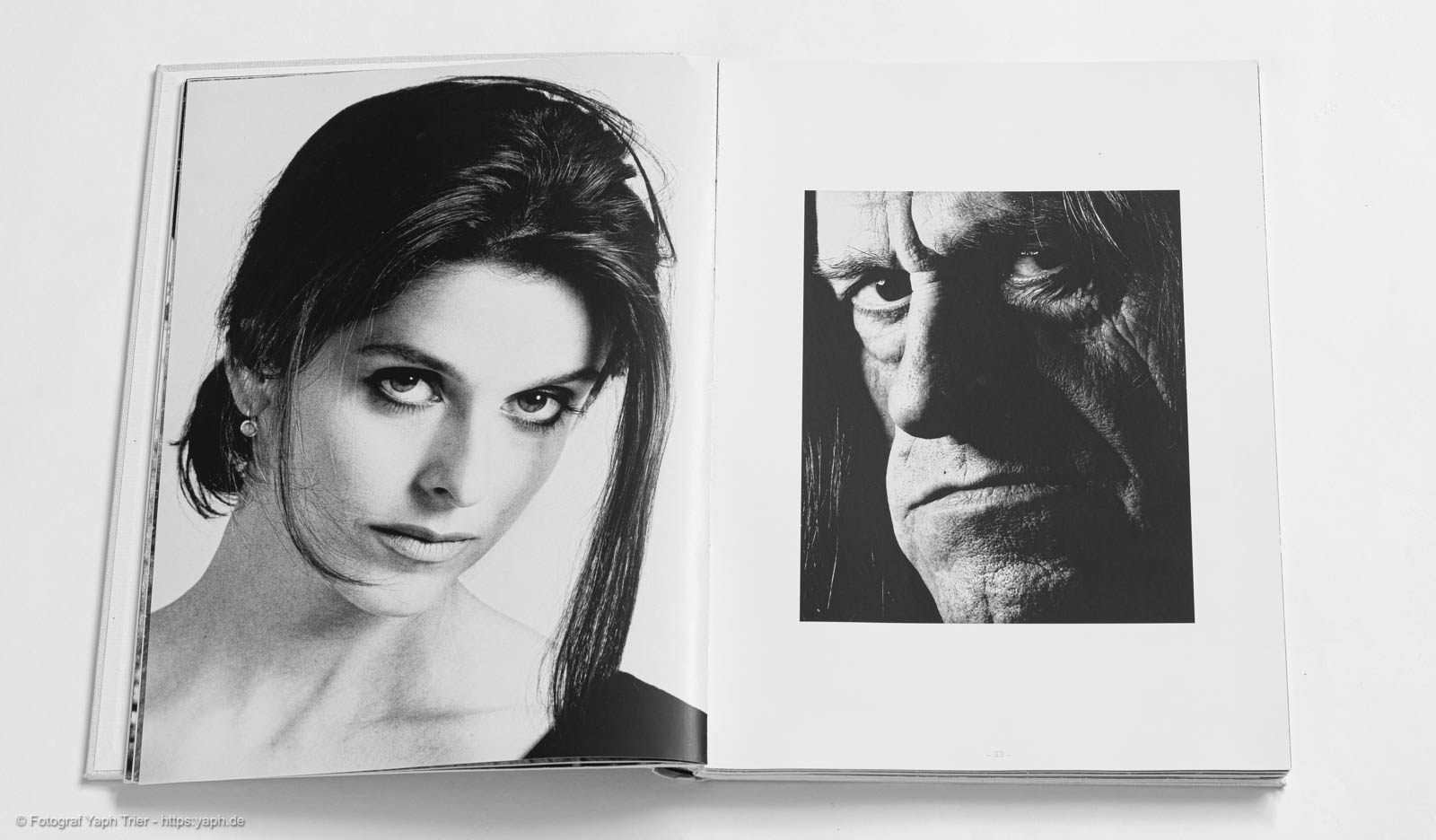

Bildband Menschen

in schwarz-weiss, 120 Seiten, 103 Triplex Tafeln

ISBN 3-929405-03-2

Fotografie: Yousef A.P. Hakimi

Text: Renate Heineck

Konzeption und Layout: Stefanie Willems

Finishing: Habib Hakimi

Übersetzung, Englisch: Gabriele Becker

Lithografie: Repro55 Trier

Druck: Nikolaus BASTIAN Druck und Verlag GmbH

Buchbindung: Schwind, Trier

Auflage: 1.600 Exemplare

“I’m longing for a keepsake from each creature on earth, of that I’ve grown fond. It isn’t only the similarity which is precious – but the connected association and the feeling of being close … the fact that the REAL OUTLINE OF THIS HUMAN BEING is kept forever. I think that is the point making portraits sacred and inviolable.

Elisabeth Barrett (in a letter to M. Russel Mitford in 1843)

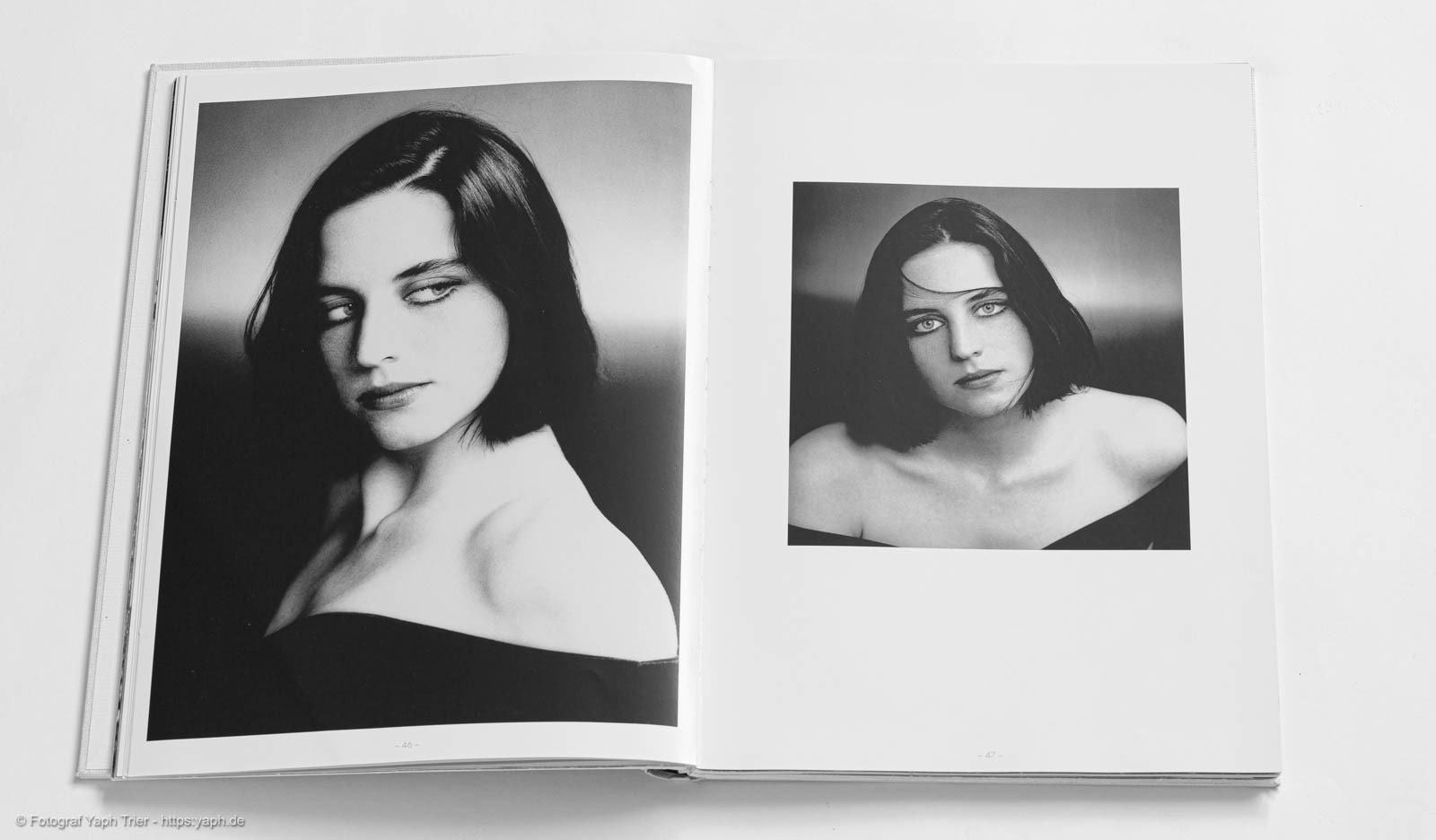

“The human face holds very much within itself. For us it is the greatest mystery and the most familiar thing. A face can express a lot without speaking. We try to read a human being’s character, nature and ego out of his face. Rage, anger, fear, sympathy and love we can see in a face. “

Yousef A.P. Hakimi (1990 to his Exhibition in Tuchfabrik, Trier)

Nearly 150 years passed between these two quotations. Nevertheless their meanings are so similar; time seems to have stood still. Nothing seems to have taken place that could point to a development. But why do these portraits still have the same appeal in our otherwise fast-moving age, attract the observer – as in the past – and occupy one’s mind again and again?

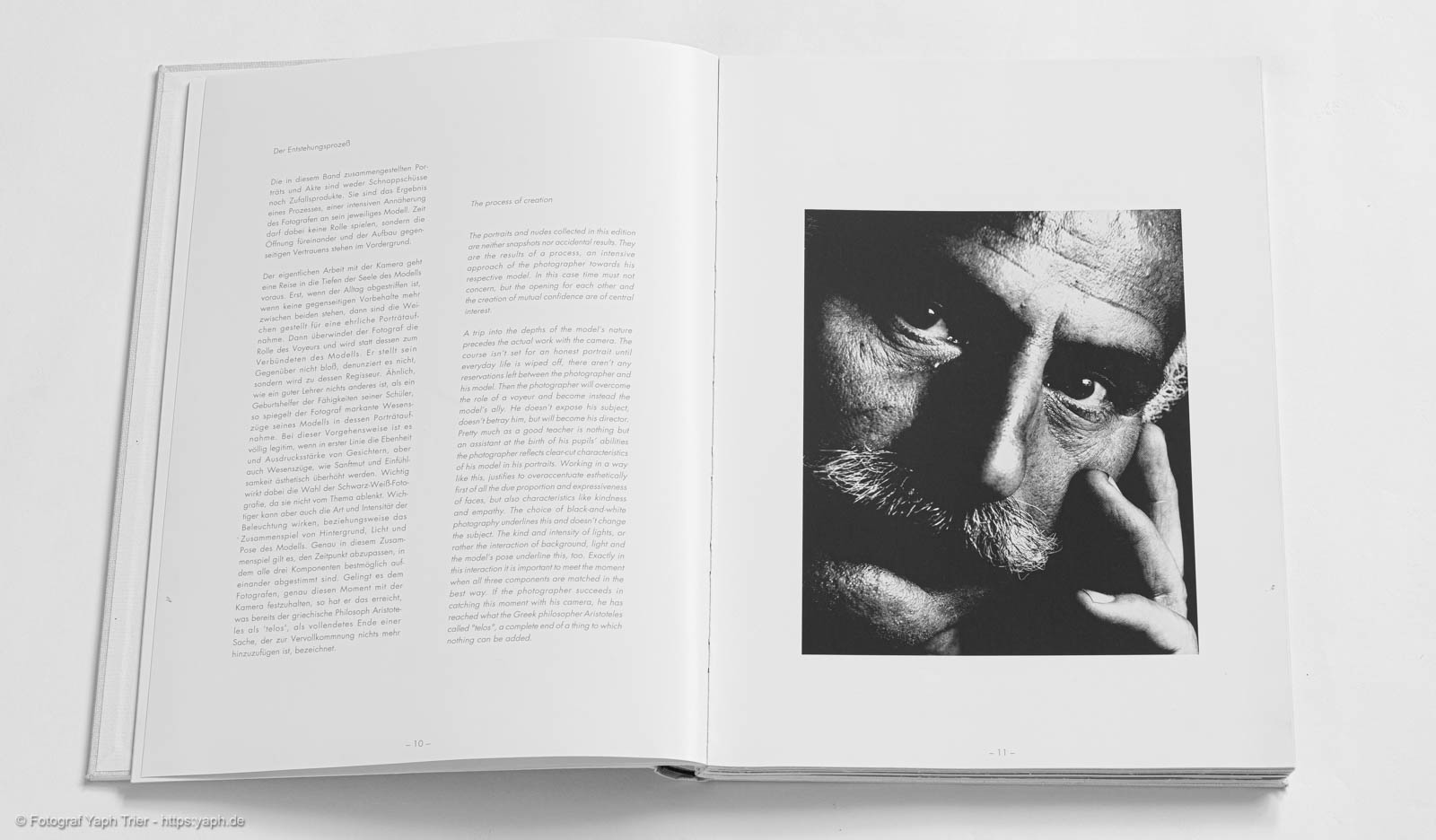

The answer is given by the object, or rather in this case the person observed: the man – the always new, always different and always unique man. The ability to appear in any variable form and to change permanently but still remaining himself, the unique, seems to be his sole privilege.

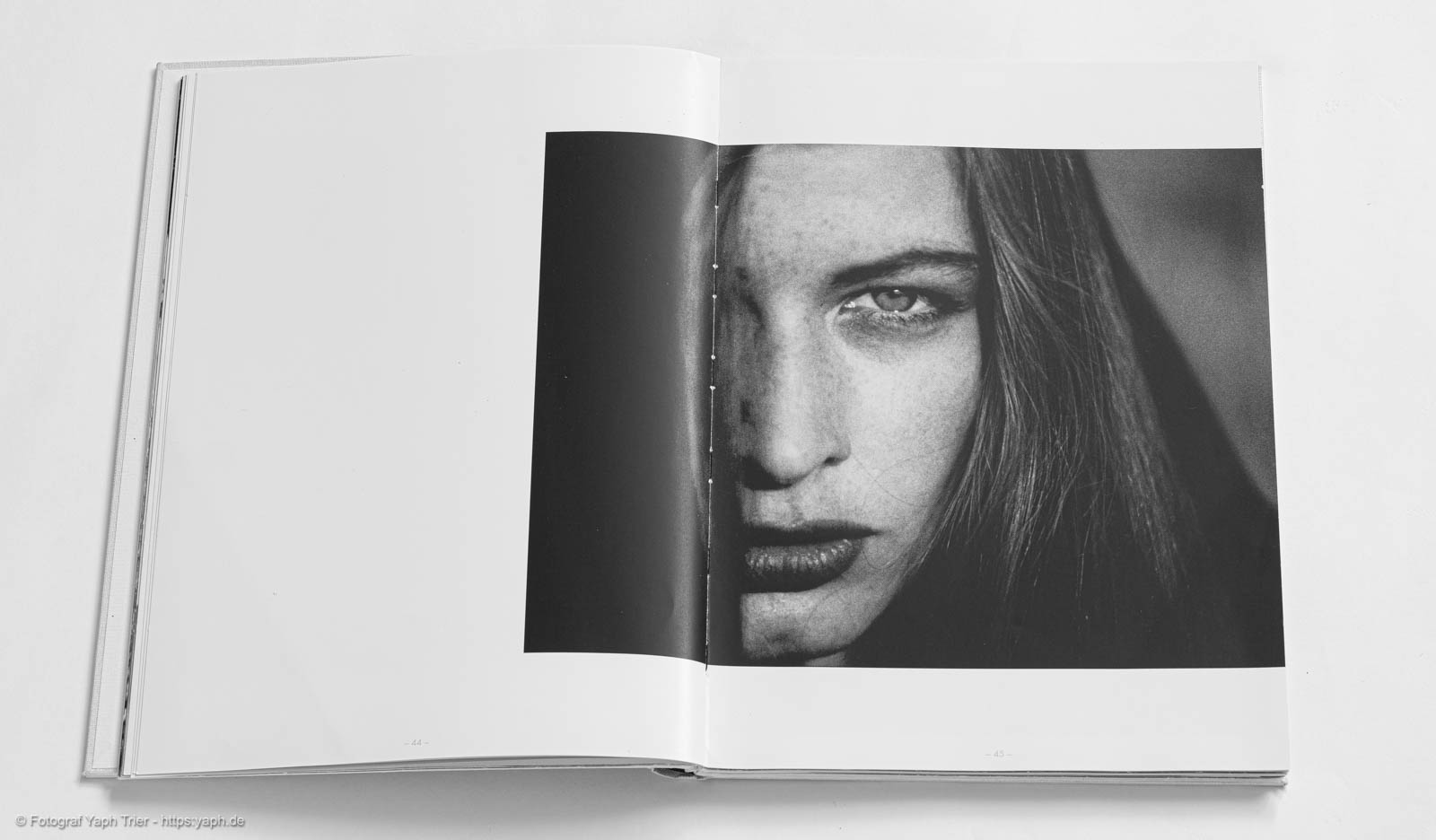

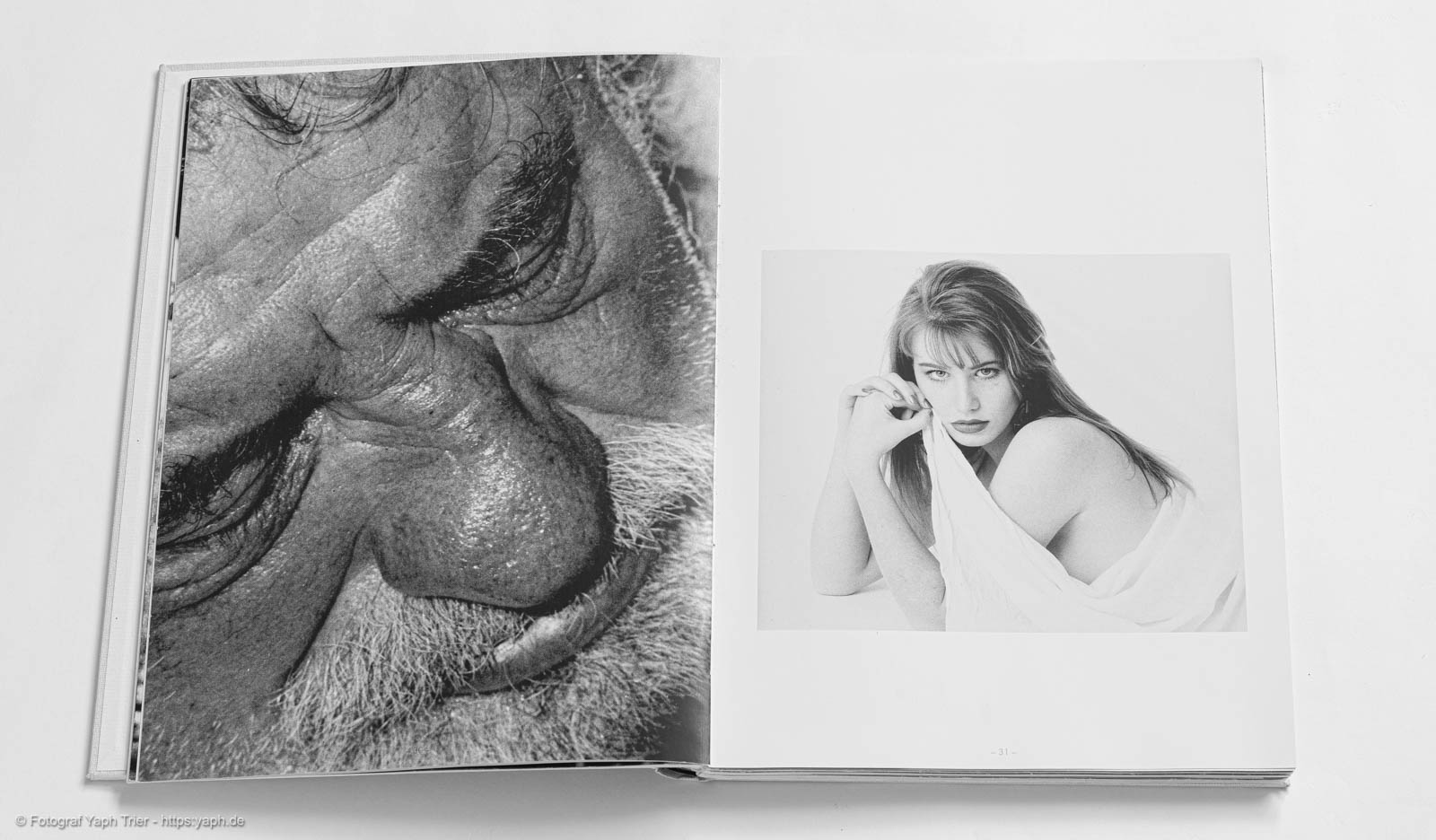

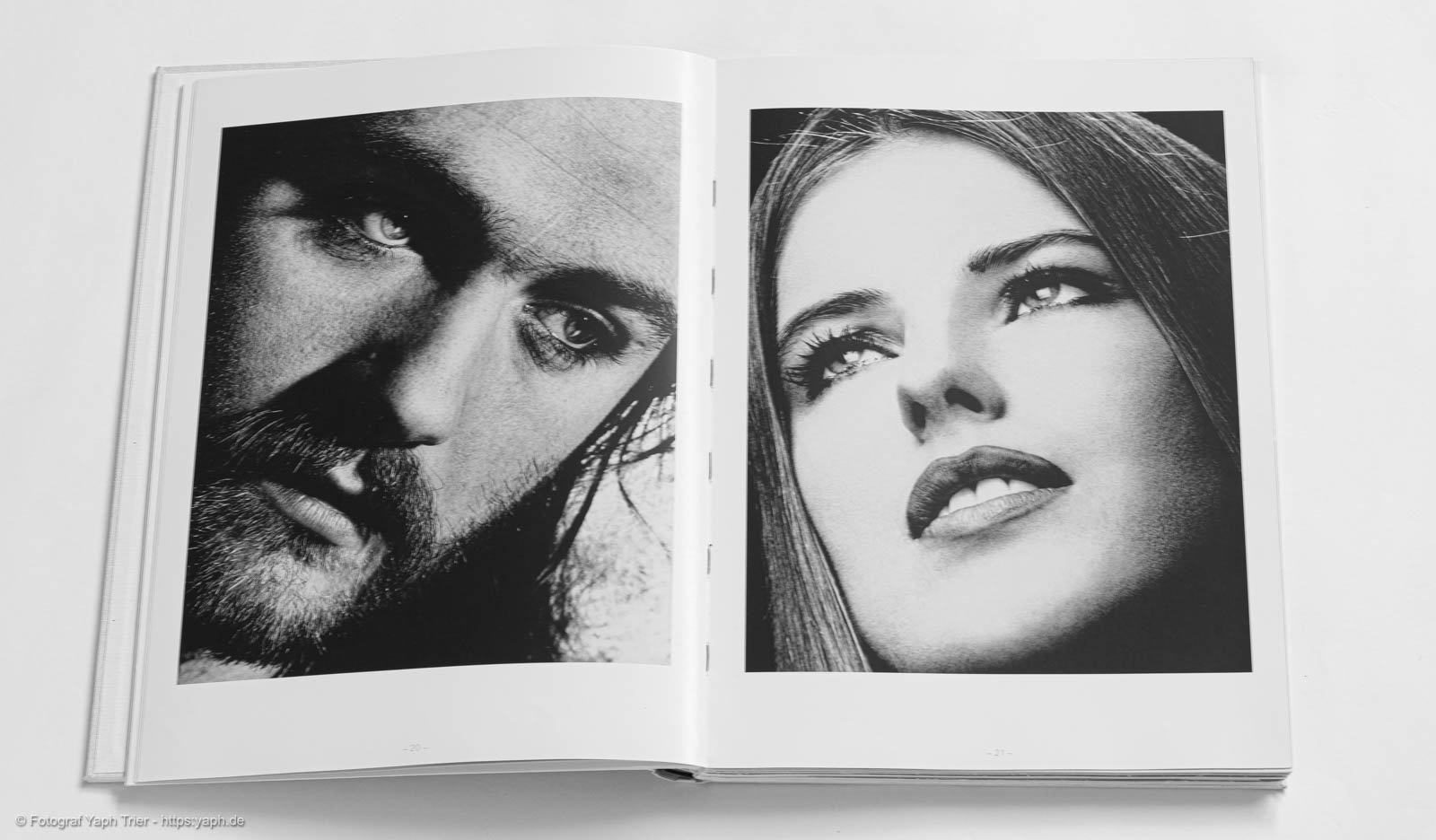

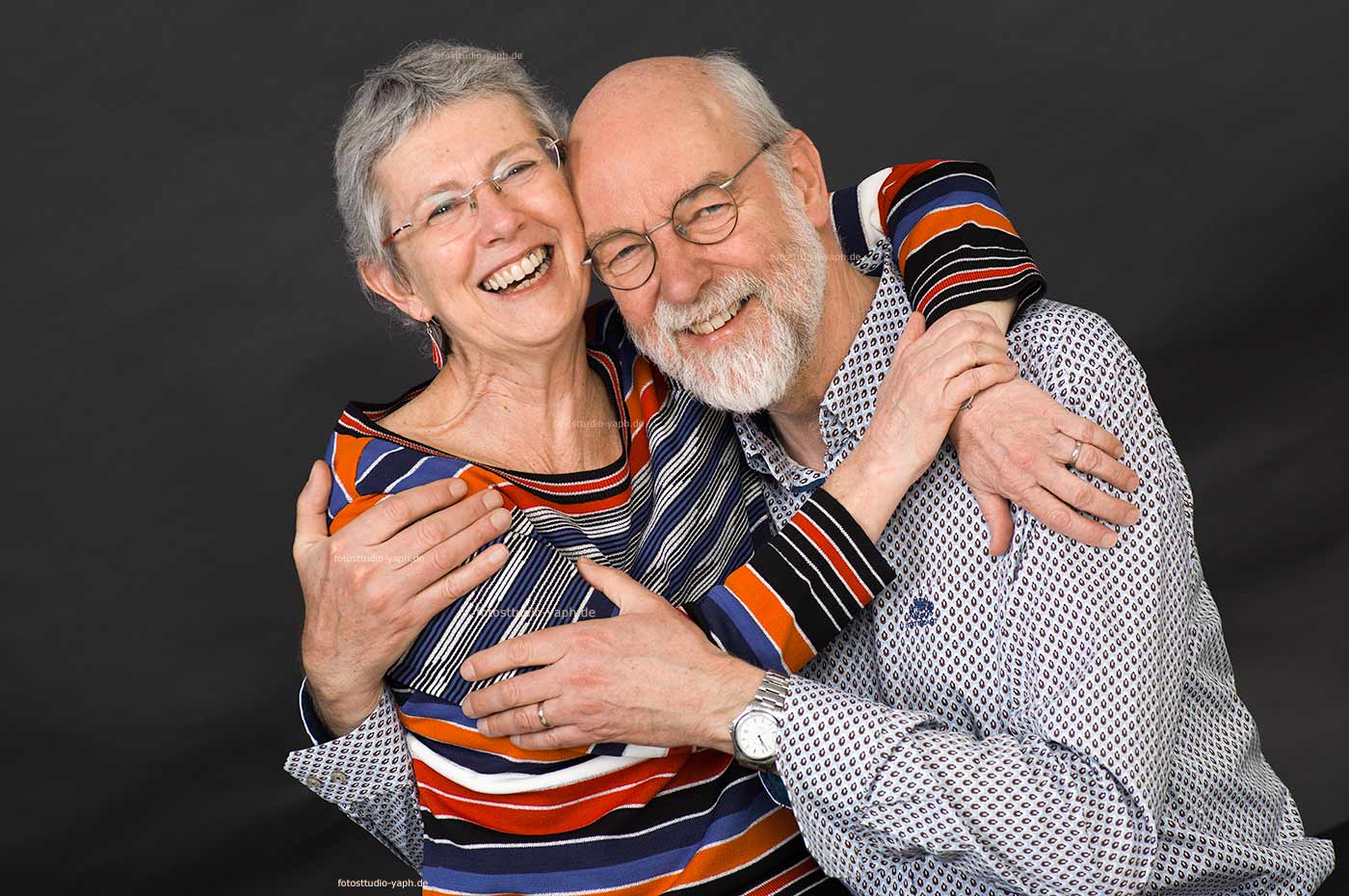

The face is the first we perceive of anybody we meet. Faces are like open books; they invite us to read, but the human being’s nature often remains hidden behind, like the messages hidden between the lines of a clever book. Portraits for example are a possibility to come closer to this nature, to lift it to the surface and to let it become visible.

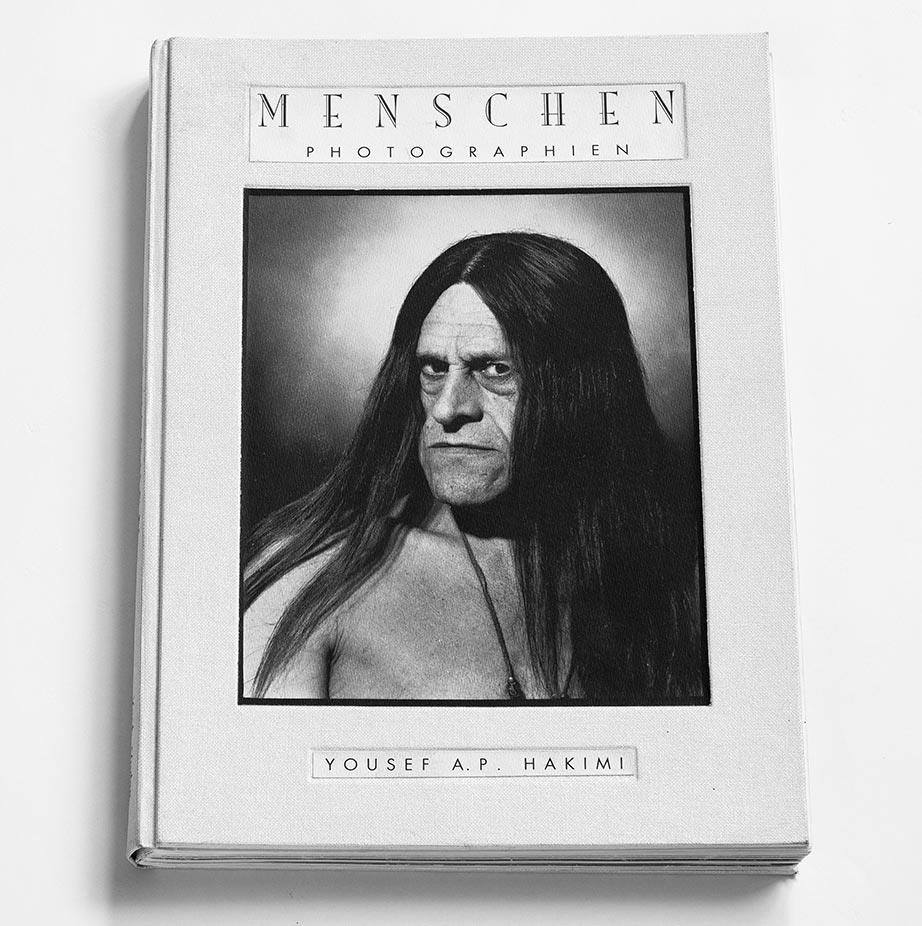

The process of creation

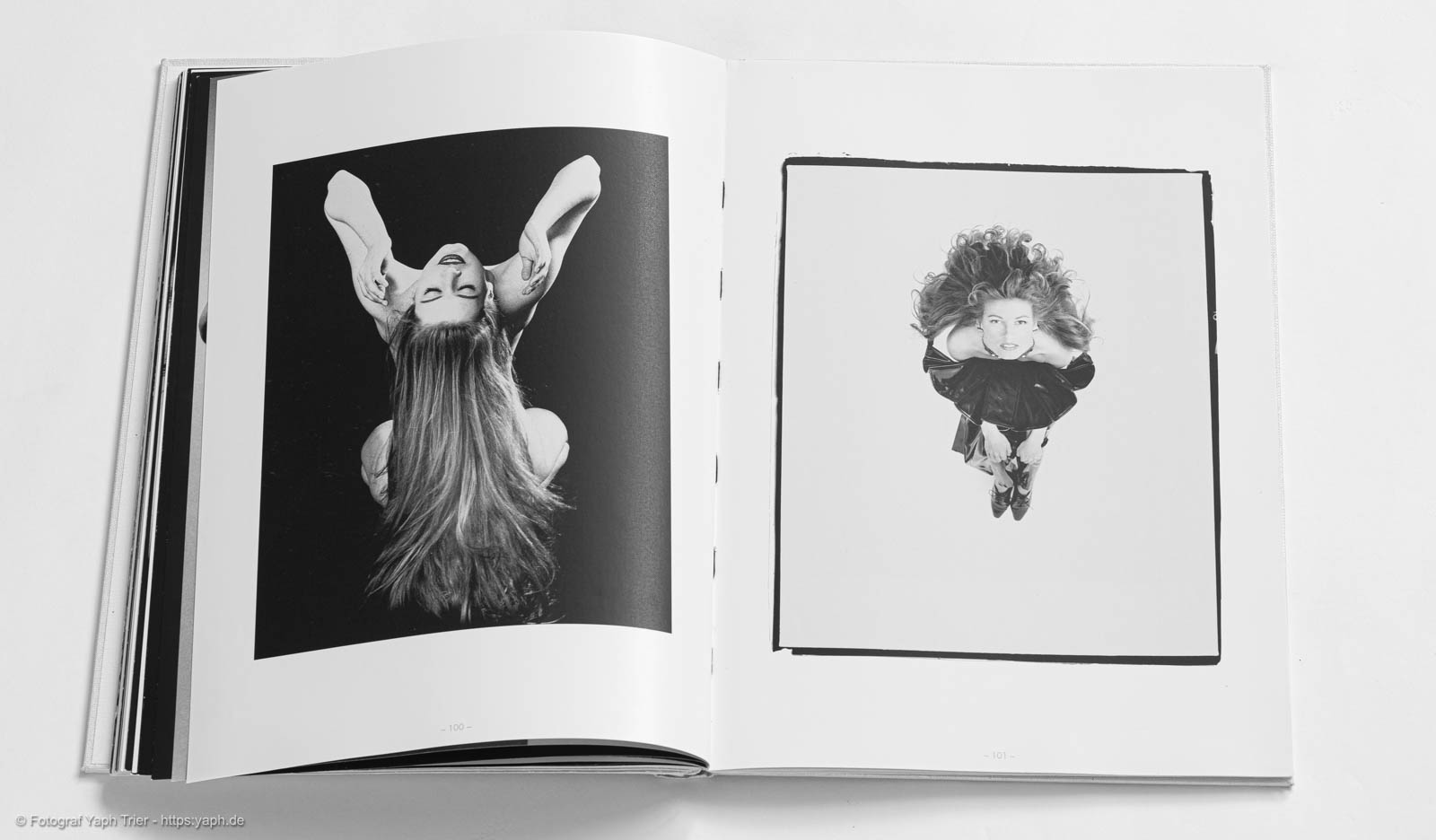

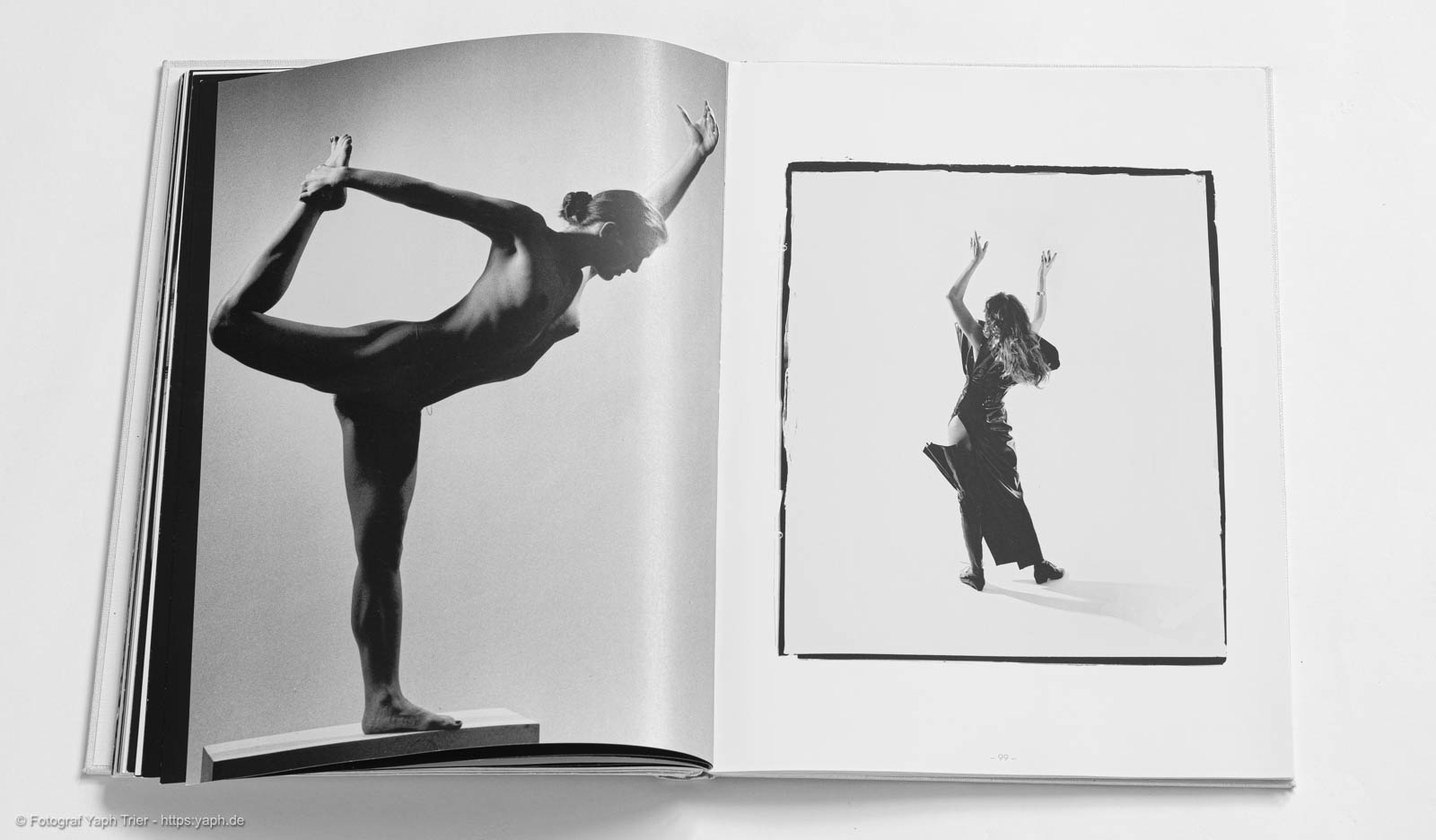

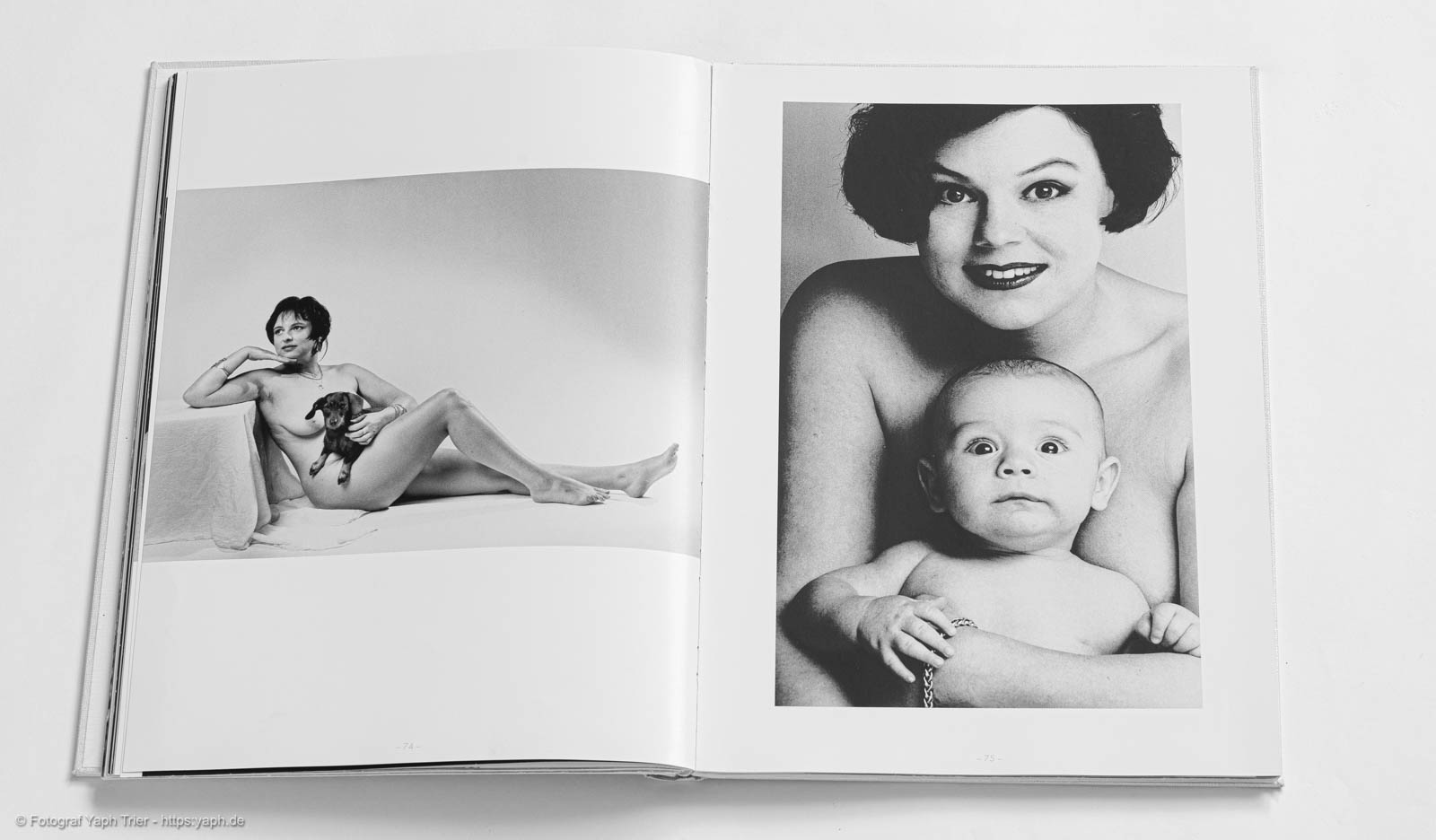

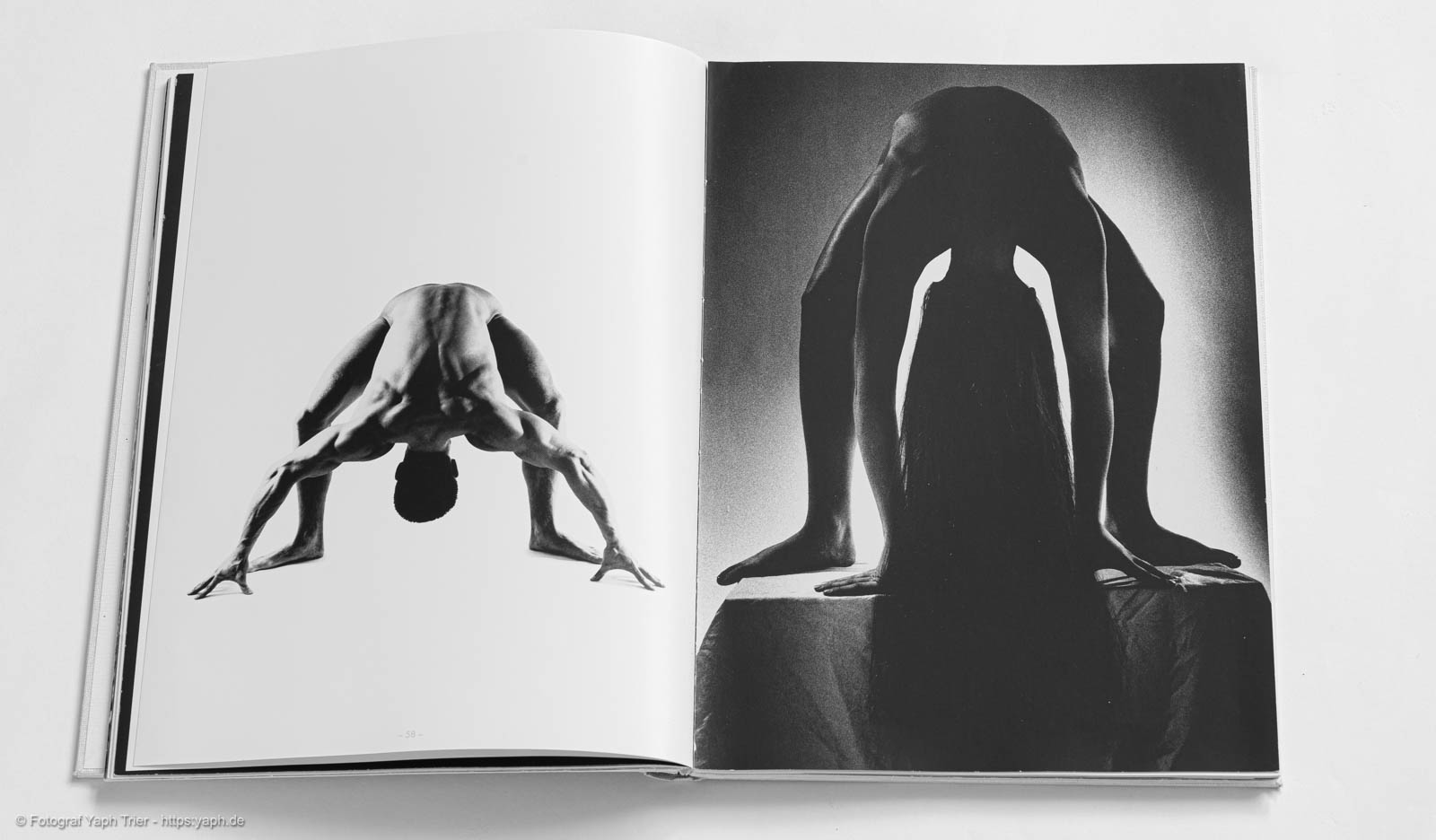

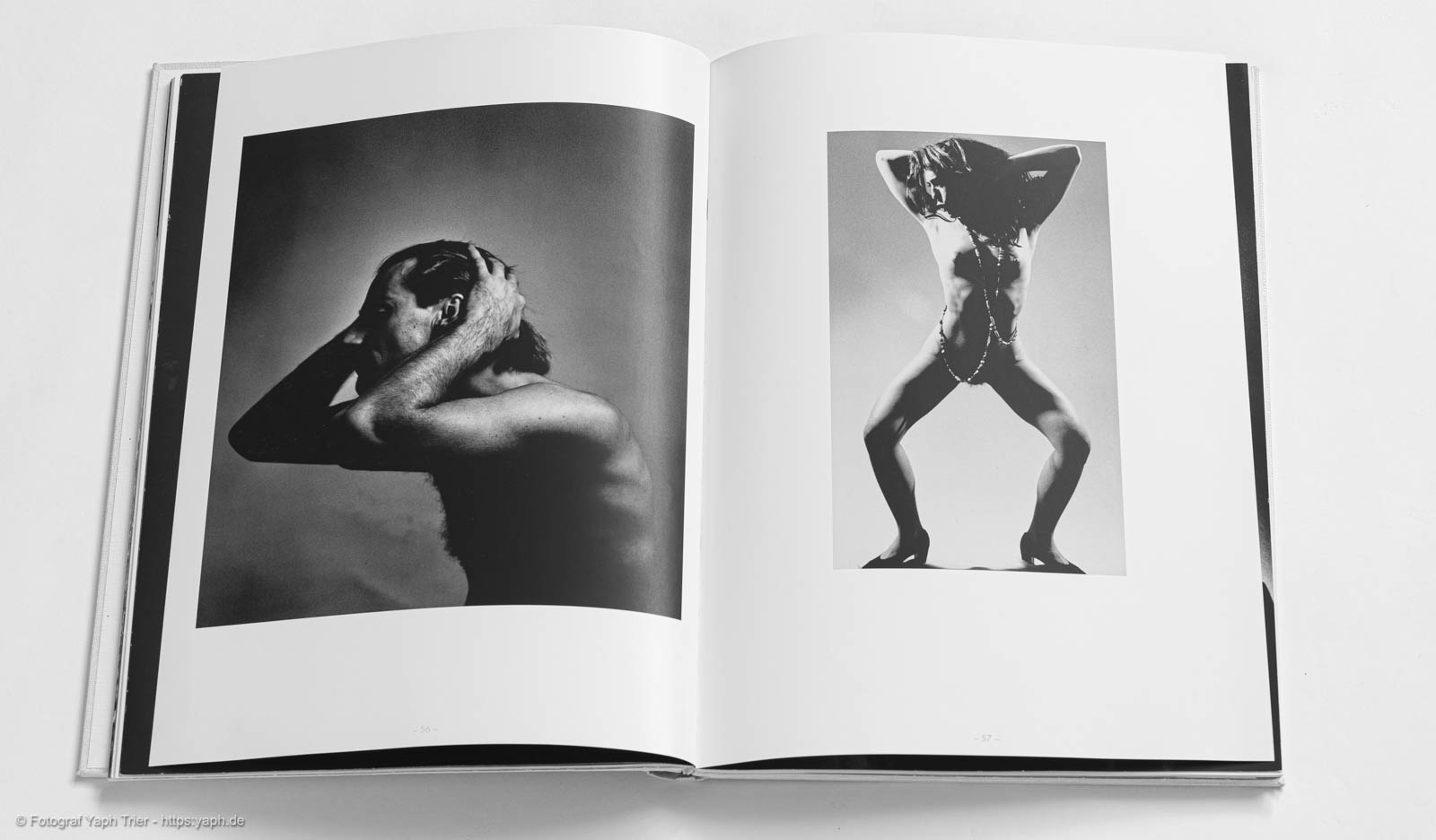

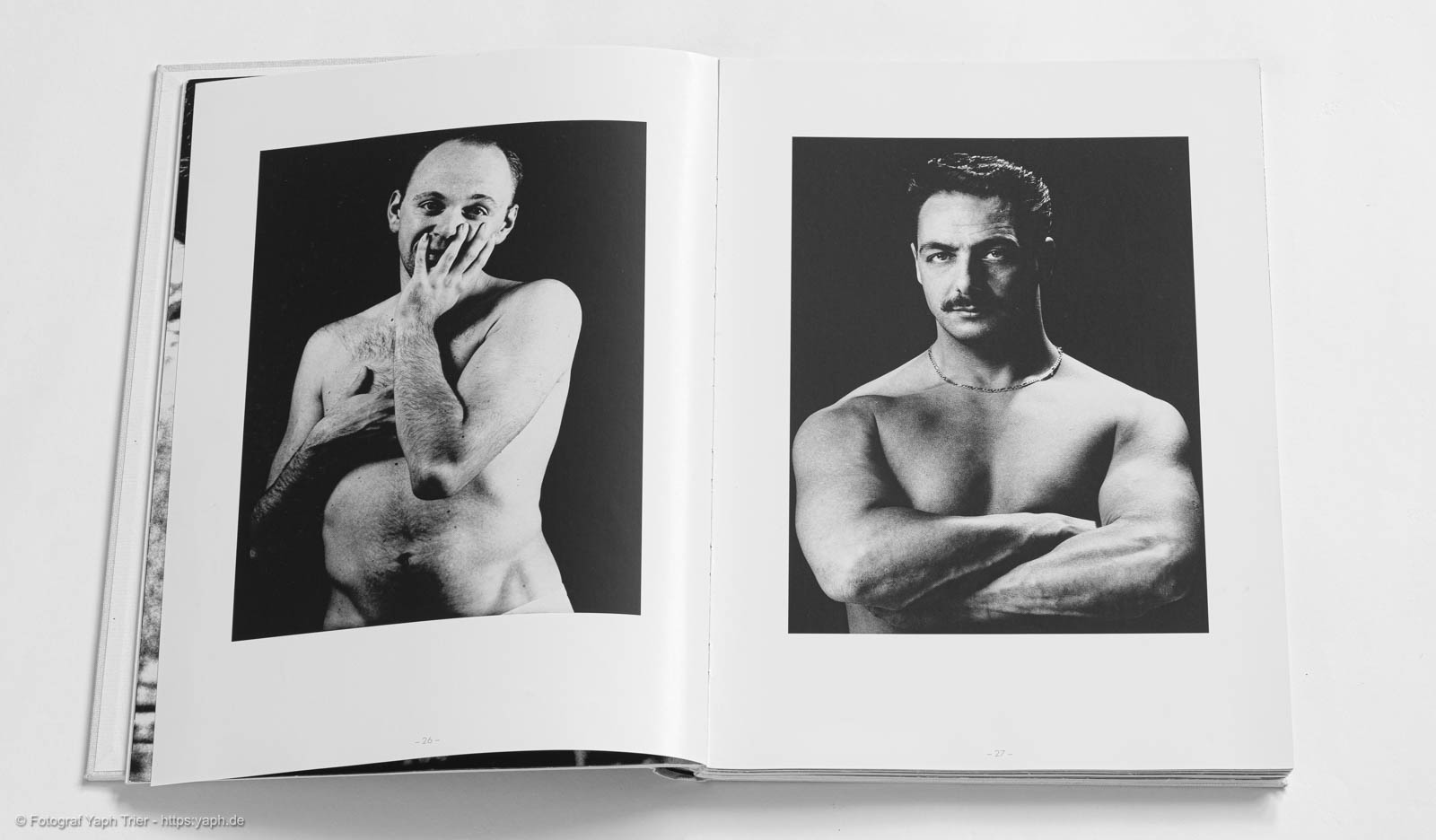

The portraits and nudes collected in this edition are neither snapshots nor accidental results. They are the results of a process, an intensive approach of the photographer towards his respective model. In this case time must not concern, but the opening for each other and the creation of mutual confidence are of central interest.

A trip into the depths of the model’s nature precedes the actual work with the camera. The course isn’t set for an honest portrait until everyday life is wiped off, there aren’t any reservations left between the photographer and his model. Then the photographer will overcome the role of a voyeur and become instead the model’s ally. He doesn’t expose his subject, doesn’t betray him, but will become his director. Pretty much as a good teacher is nothing but an assistant at the birth of his pupils’ abilities the photographer reflects clear-cut characteristics of his model in his portraits. Working in a way like this, justifies to overaccentuate esthetically first of all the due proportion and expressiveness of faces, but also characteristics like kindness and empathy. The choice of black-and-white photography underlines this and doesn’t change the subject. The kind and intensity of lights, or rather the interaction of background, light and the model’s pose underline this, too. Exactly in this interaction it is important to meet the moment when all three components are matched in the best way. If the photographer succeeds in catching this moment with his camera, he has reached what the Greek philosopher Aristoteles called “telos”, a complete end of a thing to which nothing can be added.

The result

Photographs are always only copies of reality. Nevertheless a liveliness and intensity, nearly magic, comes from an excellent photograph. We let a look capture us. We accept the invitation to read and to investigate it. The observer himself remains unobserved. We look at each other – seemingly – nevertheless we can’t see ourselves or each other. A. situation with equal rights – seemingly… And there is another common ground: just as we always perceive our reflection the wrong way round, we perceive the images of others the wrong way round, too.

It’s well-known that common grounds unite, encourage to investigate further, invite to decode the message of this moment. Thus in a second step the observer cn comprehend what the photographer put into his portrait as mediator between him and his model. An indirect communication takes place between two strangers. Ad it is amazing: the longer and more intently you look into the picture of a human being, the more diverse and detailed it will become. More and more associations seem to perfect the portrayed person. The relationship between the observer and the picture changes constantly, more and more the observer brings himself and his experiences into the interpretation. The closer the relationship, the livelier the photograph seems to become. Longing, wishes, generosity, but also diabolical cleverness, wanderlust and loneliness, all seems to be revealed gradually.

Pictures of bodies are different, as well as or especially those of nude bodies: this is particularly astonishing in times of missing taboos and sense of shame. They seem to be aware of themselves, self-contained, self-sufficient and not easily to approach or to capture. In their entirety they show a certain dignity and unimpeachability. It’s difficult to locate and to identify them. They disregard all that is dictated by the consumer world; demonstrate their own law and ideas of beauty. The body as a form and a picture as well as a part of nature, as an independent organism, as a symbol of the cosmic order and not least as a model for the human order. The photographic depiction of human beings is timeless but always innovative and current, too.

“Renate Heineck”